Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Violet Dawn

From The CFBA site:

"Paige Williams slips into her hot tub in the blackness of night...and finds herself face to face with death.

Alone, terrified, fleeing a dark past, Paige must make an unthinkable choice.

In Violet Dawn, hurtling events and richly drawn characters collide in a breathless story of murder, the need to belong, and faith's first glimmer. One woman's secrets unleash an entire town's pursuit, and the truth proves as elusive as the killer in their midst."

Brandilyn's blogsite: http://forensicsandfaith

Violet Dawn: http://www.amazon.com/exec

Scenes and Beans http://www.kannerlake.blogspot

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Something that Lasts

Didn't have time for this one, folks. But you can check it out here.

Something That Lasts: http://www.amazon.com/exec

...And James David Jordan's website: http://www.jamesdavidjordan.com

Poor Snookie

Another kvetcher I enjoy is Dick Staub at Culture Watch. I've downloaded some of his interviews at The Kindlings Muse. And he snags some great cultural influencers for those interviews--Dan Allender, David Brooks, Malcolm Gladwell, Anne Rice, Ann Lamott, as well as lesser known cultural influencers like Heidi Neumark who teaches in the South Bronx. Some are committed Christians, some are not. (If you're convinced that agnostics or aetheists are without 'soul' then you might reconsider after hearing one of these interviews.) Staub talks to them all.

And it's all commercial-free, so you get a whole lot for absolutely zilch.

Can't say that I 'enjoyed' his column today, but it certainly hit a sore spot. If you teach, or have taught anywhere--parochial or secular--do visit his column today because I can guarantee you, you've had poor Snookie in your classroom. And if you're a Christian parent who still has an ounce of influence left in your child's life, read his column today. You don't want to be creating a Snookie.

Ciao.

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Phallofemiphobia

Betcha'd love to know what that means. If you do, then hop right on over to The Review Revolution: Improving Culture Through Kvetching.

I really hope I get to meet Jana Reiss someday. Through another blog, I was directed to her latest "kvetch" on a book out by Moody Press, King Me. It's worth your time.

Also worth your time (if you haven't already caught this at Dave Long's faithinfiction blog) is Jana's Publishers' Weekly op-ed piece on violence in faith fiction. Her entry on that links to her PW piece on the subject.

Good job, Jana. Keep kvetching.

I really hope I get to meet Jana Reiss someday. Through another blog, I was directed to her latest "kvetch" on a book out by Moody Press, King Me. It's worth your time.

Also worth your time (if you haven't already caught this at Dave Long's faithinfiction blog) is Jana's Publishers' Weekly op-ed piece on violence in faith fiction. Her entry on that links to her PW piece on the subject.

Good job, Jana. Keep kvetching.

Thursday, September 14, 2006

Squat

I have more than squat to say about Squat. I just can't say it now.

Come back tomorrow. Until then, go buy the book. You won't be sorry.

Honest.

Ok. I promised a review, so here it is.

As I suggested above, I liked the book. In a world where the trend in setting and conflict seems to encourage intercontinental jet-setting in a race to counter world-wide, fascio-Islamist, anti-Zionist, bio-terror conspiracies--I welcomed Field's attempt at the good ol' classical unities of time, place, and action. Could he pull it off though?

He does. And yet, that's not the book's undoing.

Squat is set in lower Manhattan, a few years back before the area began to be reclaimed by folks who decided that New York was as cool and Seinfeld and Friends suggested, and real estate developers began gentrifying some of the borough's ghetto-lands. Before the changes, though, the world of Squat was an ugly, ignored pocket of human pus on the otherwise taught and toned public face of Manhattan.

Squid, the hero (if you will) of the novel is one of those kids who falls through the cracks of parental neglect and lands on the streets, unable to accomplish much but to collect his welfare money when he can. Appropriately, the action doesn't take Squid much further than the four or five blocks his life revolves around. And Field is smart to compress the story into a twenty-four hour period, too. If Life happens in a four block area, a Lifetime can happen in a day. Simple lives make simple choices, and Squid's day illustrates that well: he wakes knowing he stiffed the biggest bully in the neighborhood and knows the rest of the day will be a life or death proposition. No high speed car chases, no international oil money intrigue: it's a simple conflict.

Field is also smart enough to introduce some unanswered questions about charity, specifically the Christian variety. One of his characters is a street philosopher of sorts, Unc, who prides himself in asking the unaswerable questions of moral dilemmas. (A sophisticated version of the kid who always asks if God can make a rock so big He Himself can't move it.) He's a thoroughly unbelieving post-modern creature who loves the paradox for itself, and not because it points to anything greater than itself. Appropriately, when the Squid's crisis comes to a head, the street philosopher bales on him. He's 'off-stage,' hiding out on the subway line, riding from stop to stop and back again, going, but not going anywhere. It's a fitting metaphor for the character and one of the nicer touches of Field's. But Unc seems to triumph when he stumps an eager young Christian college student who comes to volunteer at the street mission. However, while Unc doesn't seem to grow, the student volunteer (through Unc's challenges) does, and he begins to rethink some of his assumptions and pat responses about God and mercy.

How Fields handles the "edgy" stuff, though, often falls flat. To conform to the CBA's standards, Fields introduces a little trick that's a new one to me: Unc the street philosopher forbids anyone to curse in front of him. That's right. The unbeliever is the prissy one with 'standards.' And because we closely follow Squid, who closely follows Unc, there's not much opportunity for any hard language to come through. Field also keeps his bad guy, Saw, off-stage for most of the book. Saw's the kind of guy who would probably turn the air blue if we actually met him--and if Field had permission (or the desire) to portray him with absolute accuracy. But instead we only hear about him or see his cohorts until the climax, so Field also side-steps that potential pile of messiness. The result is that instead of feeling increasingly threatened by a very evil menace, I felt as if Squid were being hounded by the school bully who's threatening to take away his lunch. I get to hear about Saw's reputation, and I get to visit the possible scene of one of his crimes (and he is a bad dude), but the day goes on and on with this build-up--and the build up doesn't pay off like it should.

I have no illusions that merely letting Saw step out and lay a good cussin' on Squid would solve the problem. But perhaps, in the absence of a fully-fleshed portrait of his hunter, Field failed to give me a fully realised conflict. The appearance of light is increased in contrast to the darkness it illuminates. And while Field does try, I think this book would have been better served by letting us truly see the dark Squid is fighting to escape. Perhaps it would have been a blunter presentation, and it most likely would have been a shorter tale. But I think it would have served the message better. Instead of saying "Wow," I feel a bit like I got led around on a New Orleans Katrina tour: Look at the terrible things that happened here; isn't it a shame? Don't get out now, there's toxic waste beneath these tires, and you wouldn't want that on your shoes, would you? I got to look, but I didn't get to touch.

Did I like Squat? I did; for all my criticism here, I really did. Here's why: for all the talk about this being a book about those poor unfortunates who're left homeless and helpless, this is really a book about you and me. For all our probably middle class standards, and for all the things we take for granted about travelling and eating and friendship and love--we all live in a world like Squid's, bounded by experience and our personal limitations. We live with names not of our own choosing, and reputations not always of our own making. In small or large ways, the world has forsaken all of us, somehow. And even when we claim the Christ for our own, we must work to escape the ghettos of our own sins. If you missed that point, rethink the book. Don't, don't miss it, folks. This ain't no tour bus you and I are on, and in the end--whether Field is happy or not with what I perceive are the limitations of this work--this is what the author wants you to know.

http://squatbook.wordpress.com/

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0805432922/

Friday, September 01, 2006

First Novels, continued

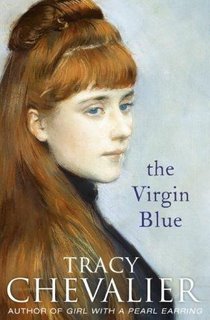

"It got a few small reviews, sold a few copies, then sank to the bottom of the pond to live with all of the other unnoticed novels." --Tracy Chevalier, on the life of her first novel, The Virgin Blue

"It got a few small reviews, sold a few copies, then sank to the bottom of the pond to live with all of the other unnoticed novels." --Tracy Chevalier, on the life of her first novel, The Virgin BlueFortunately for Chevalier, she survived on the modest notice of her first book to write her second--The Girl with the Pearl Earring, a book that attracted enough popularity and attention that it was developed into a film with Scarlett Johannson and Colin Firth. (I suppose anyone who's finally published that first novel, only to have it disappear into obscurity, can read this and take heart in the possibility that somehow, some way, a second effort will find its proper audience. Like, um, with a major film studio...)

But before that success Chevalier was only a novice novelist with glowing reviews from the Brits and scathing reviews stateside. Fortunately I'd never read those bad reviews before I got my hands on this recently republished first effort. I haven't read Girl, so the Chevalier experience was totally new to me, and I came to it with no preconceived notions.

As I've said before, I partial to historical novels, and if you can throw in a bit of romance and mystery as well, then I'm really happy. And on that score, Chevalier made me mostly happy.

The story is basically this: a 20th century American wife moves to France with her ambitious architect (also American) husband and, when they try to start a family the wife begins having powerful nightmares (which feature a distinct color of blue), she tries to overcome them by seeking out the meaning of the dreams. The search eventually uncovers secrets of her 16th century Hugeunot ancestors and undoes her marriage. Intercut with the 20th century action is the 16th century (waaay) backstory.

The problem was, once I got past the set-up, I could too easily see what Chevalier was attempting with her double cast. We are first introduced to Isabelle in her 16th century world, and then her 20th century descendent, Ella. Isabelle/Ella--get it? If you can live with that sort of obvious parallelism, then you won't be distracted by the rest of the literary doppelgangers she threads throughout the story. This can be fun for the reader, but here it seemed a little too neat.

[Warning: spoilers involved now!]

I didn't empathize with Ella, either. While her quiet war with the gossipy French villagers amused me, I couldn't accept, on any terms, her affair with the librarian. While I'm totally against adultery and acknowledge its destructiveness to all involved, sometimes I accept (note, I do not enjoy) a character's adulterous behavior because it is consistent with that character's morality. It makes a believable story. But Chevalier didn't convince me that Ella's husband was anything more than a well-meaning dolt, and we're left wondering why she married him in the first place. Because of this, the character arc of Ella falling out of one love and into another seems more like it's meant as a comment on her ancestor's marriage than her own.

But I got over all this because I really loved Isabelle, and I enjoyed Chevalier's style. It's in the 16th century that the author really gets the reader involved. Isabelle is a woman of private convictions and great personal strength, living as an outsider as the daughter-in-law of a wealthy, but not noble, Huguenot family. The virtual imprisonment Isabelle suffers in the home of her abusive husband and her suspicious, superstitious mother-in-law is enough for a reader to want to whap 20th century Ella upside the head for all her shallow grumbling about "he doesn't get me." It's a comparison that doesn't do our modern heroine any favors.

Chevalier is also much more adept at showing us complex characters, who, when faced with real persecution and oppression, make complex decisions. Her 16th century characters are all believers who mix pragmatism and politics in with their choices, allowing (as Chevalier presents it) a kind of syncretism in their daily practices that's not often recognized from our modern pulpits. But I buy it because it's human nature to mix a little bit of the old gods in with the new. The consequences for us in the 21st century are as destructive as they are in the 16th. Unfortunately Chevalier's lightweight treatment of Ella's choices is hardly worthy of her ancestor's heartbreaking sacrifices and ultimate fate.

If you'd like to chew over these ideas and you're up for a little history, a little mystery, and an introduction to Chevalier's "clean prose style," I recommend the book. For all it's faults, it's still a good tale, and if I could do this well my first time out, I'd be a happy girl.